Microplastic pollution has emerged as one of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time, captivating public attention with haunting images of marine wildlife ensnared in plastic debris. However, the reality of plastic waste in the oceans extends far beyond what is visible on the surface. Numerous studies indicate that the volume of plastic entering the sea each year could reach up to 12.7 million tons, stemming from both land-based sources—such as rivers—and maritime activities, including fishing and shipping. An intriguing recent study has focused on the North Sea, which has proven to be a significant repository for these toxic particles.

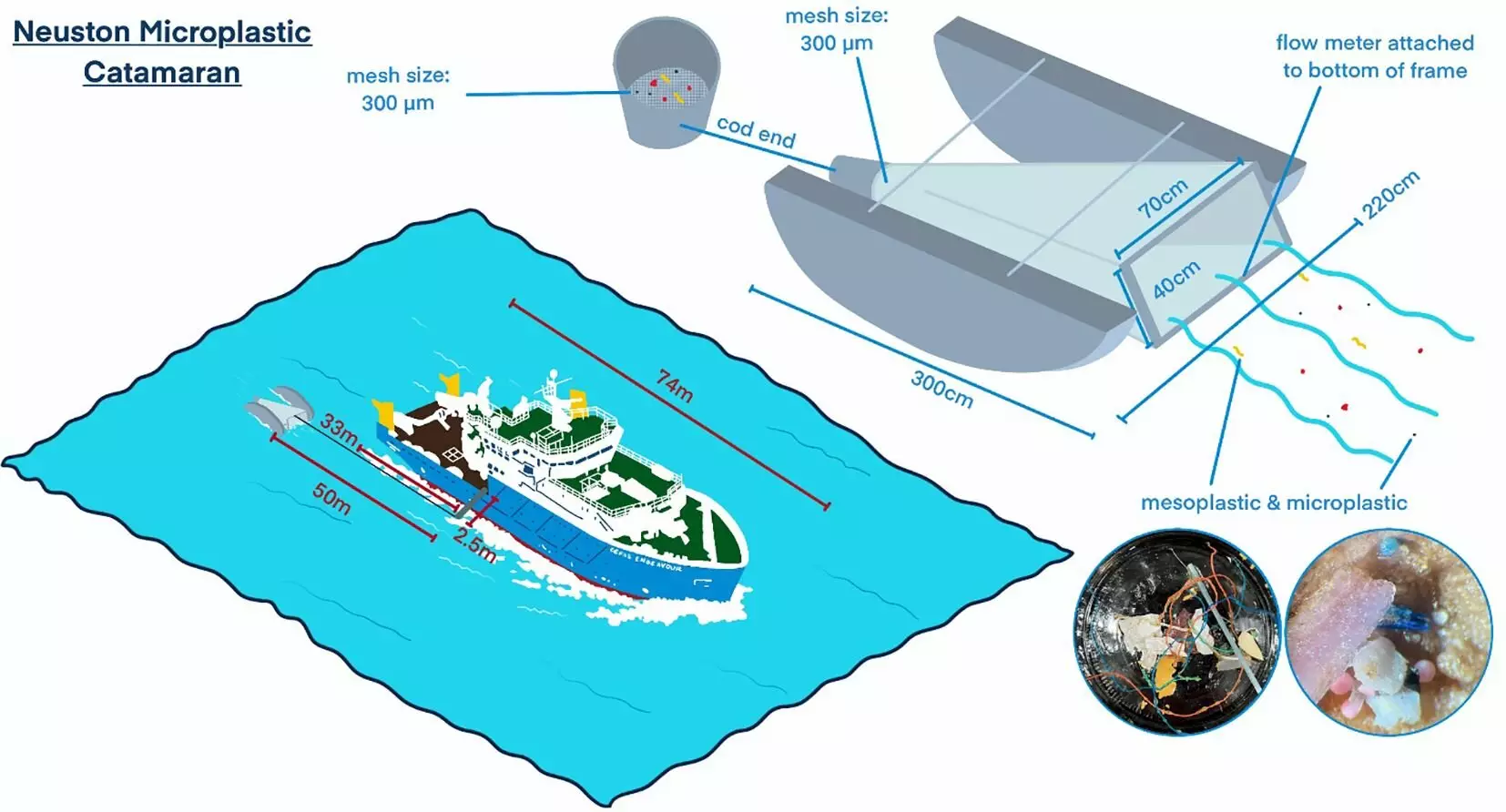

Research led by Dr. Danja Hoehn at the Center for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (CEFAS) has utilized innovative technology to assess microplastic distribution in the North Sea. Employing a specialized device known as a Neuston Microplastic Catamaran, the research team gathered data from the ocean’s surface in 2022. This technology is pivotal for capturing and analyzing microplastics, which are known to enter the ocean primarily through terrestrial runoff or as debris from vessels.

The findings revealed alarmingly high concentrations of microplastics, particularly in the Southern Bight of the North Sea. With peaks reaching over 25,000 particles per square kilometer, the research illustrates a stark contrast with adjacent offshore locations. For instance, the waters around Scotland exhibited a substantially lower mean concentration of approximately 4,500 items per square kilometer. This not only highlights the presence of microplastic pollution but also raises questions about the marine currents and their role in transporting plastics across vast distances.

The Composition of Plastic Pollution

Understanding the composition of microplastics is critical for developing strategies aimed at mitigating their detrimental effects. The study indicated that the predominant forms of microplastics included polyethylene fragments, which accounted for 67% of the findings. This particular type of plastic is alarmingly ubiquitous, found in common household items ranging from shopping bags to children’s toys. Following closely behind were polypropylene and polystyrene, accounting for 16% and 8% respectively, both of which are widely used in packaging and consumer goods.

Moreover, while smaller microplastics (less than 5 mm) dominated the dataset, larger sizes—referred to as mesoplastics and macroplastics—were also present. These larger fragments indicate the breakdown of bigger plastic items, showing the continuing cycle of pollution and the subsequent risk they pose to marine ecosystems. Despite the UK’s ban on microbeads in cosmetics since 2018, traces of this plastic persist in the environment, likely carried over by oceanic currents from countries where usage remains permissible.

The implications of microplastic pollution are dire, not only for marine wildlife but also for human health and ecosystem integrity. The hotspots identified off the coast of East Anglia signify critical regions requiring urgent attention and action. Notably, despite the high levels in the North Sea, concentrations are significantly lower than alarming figures reported elsewhere—such as 1 million items per square kilometer in the Canary Islands—a reminder of the global nature of this crisis.

Active initiatives aimed at combating marine pollution are already underway on various fronts. The UK’s Marine Strategy, which seeks to develop indicators for microplastics in sediments, exemplifies national commitment to addressing this issue. Concurrently, the United Nations Environmental Agency has set ambitious goals, advocating for a legally binding agreement targeting plastic pollution by 2040. Collaborative international efforts will be essential, particularly given the exceeding global demand for plastics—approximately 400 million tons annually.

Understanding the scale and impact of microplastic pollution is critical for the future of our oceans. With rich marine biodiversity at stake and the looming threat to human health, it is essential that governments, industries, and communities rally together to implement comprehensive strategies aimed at reducing plastic usage and enhancing waste management. The evidence from the North Sea illuminates just one aspect of a much larger problem—one that necessitates immediate and sustained global action. As stewards of the planet, we hold the responsibility to protect our oceans, ensuring they can thrive for future generations.

Leave a Reply