Water scarcity is emerging as one of the most pressing crises facing our planet. With climate change exacerbating drought conditions and population growth increasing demand, the quest for sustainable water management has never been more critical. Researchers from Stockholm University have introduced a groundbreaking perspective on assessing global water risks, shifting the focus from traditional understandings of water supply to a more nuanced view that considers the conditions of upwind ecosystems where rain originates.

The conventional view of water security typically involves evaluating the rainfall that replenishes rivers, lakes, and aquifers. This model is fundamentally shortsighted. It fails to recognize that the moisture that leads to precipitation is not inherently produced in the vicinity of the water bodies it replenishes. According to Fernando Jaramillo, an associate professor at Stockholm University, the moisture which falls to earth as rain is largely dependent on upwind conditions. These conditions are critical in determining the availability of water supply but are often neglected in traditional assessments.

The concept of a “precipitationshed,” an area from which moisture is sourced before it precipitates as rain, plays a pivotal role in this new understanding. For example, in the Amazon basin, many regions that rely on its ecological services for water are situated downwind from the Andes Mountains, which themselves depend on the moisture produced by the Amazon. This interdependence signifies a complex web of hydrological relationships that traditional assessments do not adequately address.

New Research Findings

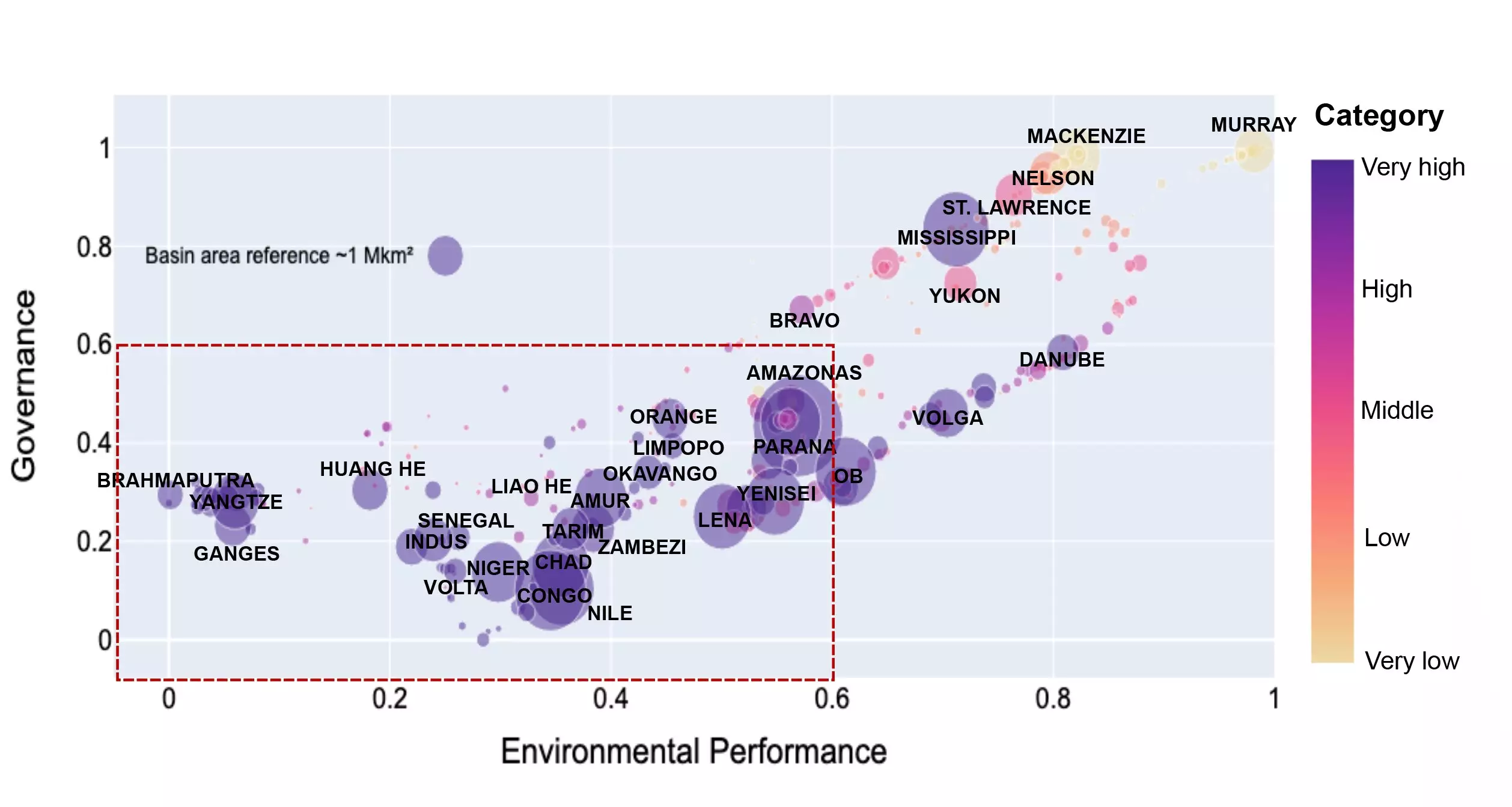

The study led by Jaramillo and his team examined 379 hydrological basins across the globe. Their findings present a sobering picture: when evaluating water risks from an upwind perspective, the demand for water facing significant scarcity jumped dramatically from 20,500 km³/year to 32,900 km³/year, indicating a nearly 50% increase in vulnerability. This metric is alarming, as it underscores that the global supply of water is more precarious than previously thought.

Central to the research is the realization that human activities in upwind regions significantly influence the availability of moisture and, ultimately, rainfall in downwind areas. For instance, increased deforestation or changes in agricultural practices can greatly diminish moisture levels, which in turn reduces precipitation downstream. Jaramillo emphasizes this point, noting that countries with landlocked positions, like Niger, often rely heavily on moisture evaporation from neighboring nations, making their water security particularly precarious amid changes in land use.

Conversely, coastal countries like the Philippines, which derive much of their rainfall from ocean evaporation, might experience less risk from land use changes on land. This distinction highlights the need for a tailored approach when assessing water security based on geographic and environmental contexts.

Governance Matters

Beyond environmental factors, the study explores the significance of governance in water management. Poor environmental governance in upwind countries can have dire repercussions for downstream nations. The Congo River basin serves as a stark example; it is heavily reliant on moisture from its neighboring countries that often lack effective environmental regulations.

Co-author Lan Wang-Erlandsson draws attention to this interconnectedness, stressing the importance of cooperative governance frameworks between countries. He argues that the political climate in one nation can have cascading effects on the water resources of others, underscoring the necessity for collaborative international management of shared water supplies.

Looking to the Future: International Cooperation

The findings of this study serve as a clarion call for a thorough re-evaluation of water security strategies worldwide. The complexity of water systems mandates a broader perspective that integrates upwind moisture sources into governance frameworks. The interconnected nature of our water supply means that countries can no longer afford to adopt isolated management practices. Instead, they must engage in cooperative efforts, sharing knowledge and resources to mitigate potential water crises stemming from upstream activities.

As Jaramillo and his colleagues advocate, the time has come for international cooperation that transcends borders, ensuring that water resources are sustainably managed from their sources right through to consumer use. Only through a shared understanding and proactive strategies can we hope to secure the planet’s most vital resource for future generations.

Leave a Reply