In the realm of biotechnology, bacteria have long been viewed as potential powerhouses for sustainable production. These microorganisms can synthesize valuable materials, such as cellulose, silk, and various minerals. The advantages of using bacteria are compelling: the processes typically unfold at room temperature, require only water, and harness biological methods that are inherently renewable. However, this biological alchemy comes with its own set of challenges. The production speeds can be lackluster, and the yield often falls short of what is necessary for large-scale industrial applications. In light of these hurdles, there has been a concerted push among researchers to engineer these microscopic entities into living factories, thereby drastically increasing their output.

Innovative Approaches to Bacterial Engineering

The quest for improved bacterial strains has given rise to groundbreaking methodologies, notably one from a team led by Professor André Studart at ETH Zurich involving the cellulose-producing bacterium, Komagataeibacter sucrofermentans. By leveraging the principles of natural selection, this research group has found a method to generate hundreds of thousands of bacterial variants in a remarkably short timeframe, enabling the identification of strains that excel in cellulose production.

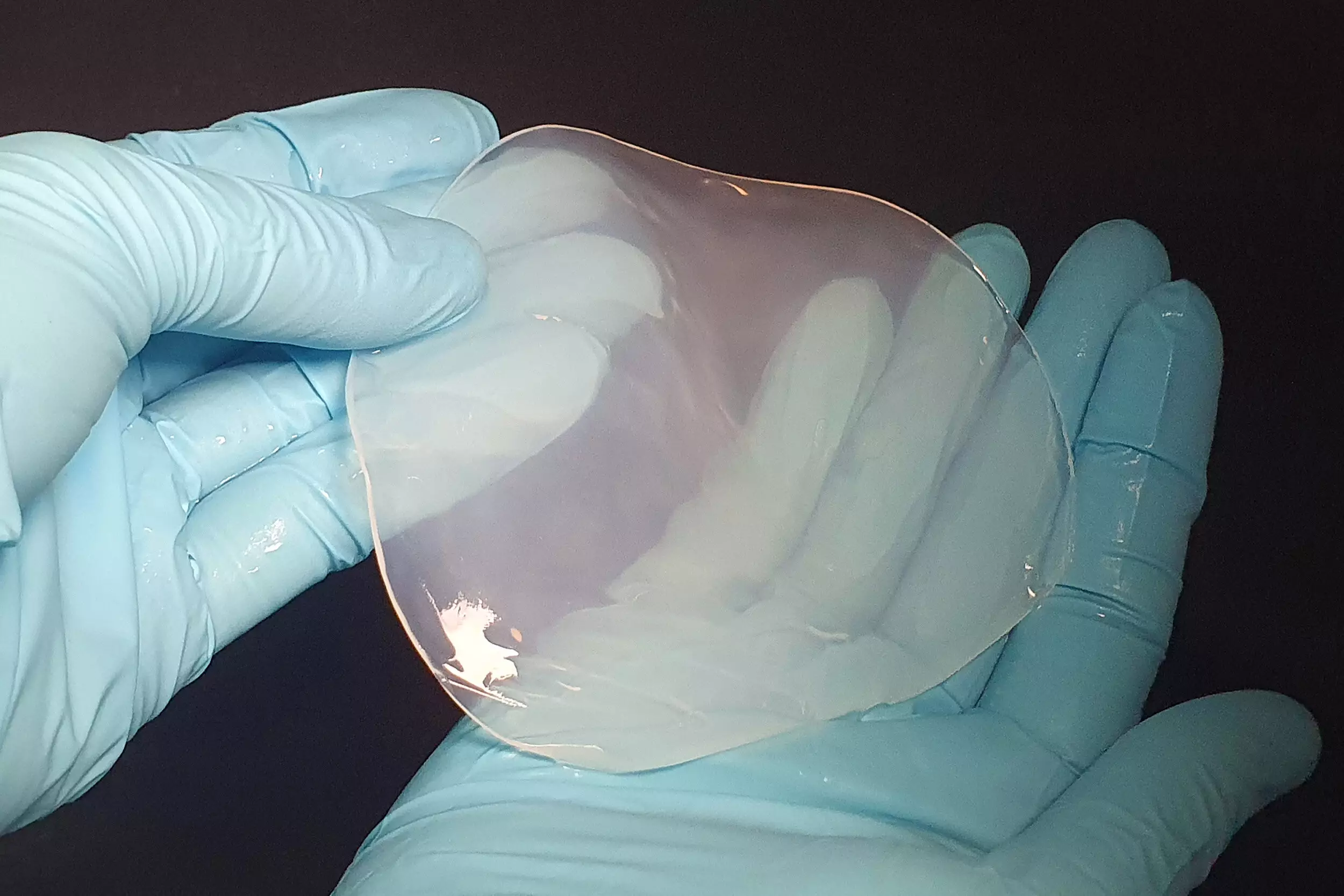

K. sucrofermentans is particularly noteworthy for its ability to naturally yield high-purity cellulose—a substance in escalating demand across various industries, encompassing biomedical applications, textiles, and eco-friendly packaging. Cellulose sourced from this bacterium has exceptional properties that promote wound healing and minimize infection risks, making it even more valuable in medical contexts. However, the inherent slow growth rates and limited cellulose yields of this bacterium necessitate innovative solutions to bolster production capabilities.

A Breakthrough Methodology: Accelerating Cellulose Production

Julie Laurent, a doctoral candidate in Studart’s group, has spearheaded a groundbreaking study toward enhancing bacterial cellulose yield. Her approach involved irradiating the K. sucrofermentans cells with UV-C light, creating random mutations in their DNA. By placing these irradiated cells in a dark environment, she prevented the repair mechanisms from kicking in, thereby fostering a higher degree of genetic variability. This strategic manipulation is critical for identifying variant strains capable of superior cellulose production.

Following this genetic stirring, Laurent encapsulated individual bacterial cells within minute droplets of nutrient solution. After allowing these encapsulated cells to produce cellulose over a designated time, she employed fluorescence microscopy, a sophisticated imaging technique, to analyze the results. This process enabled her to distinguish high-producing strains from their less productive counterparts. The study integrated an advanced sorting system developed by chemist Andrew De Mello, allowing rapid laser-based screening of up to half a million droplets in mere minutes to isolate the most productive cells.

The results were striking: only four evolved strains exhibited cellulose production rates exceeding those of the original wild type by 50 to 70 percent, marking a significant leap forward in bacterial bio-manufacturing.

The Genetic Secrets of Enhanced Cellulose Production

Upon further examination of the selected variants, Laurent and her colleagues conducted genetic analyses to uncover the specific mutations responsible for the observed yield improvements. Intriguingly, all four evolved strains shared a common mutation in a gene encoding a protease, an enzyme involved in protein degradation. This revelation suggests an unexpected regulatory pathway: although the genes directly governing cellulose production remained unchanged, it is hypothesized that the protease may degrade proteins that modulate cellulose synthesis. Essentially, by removing regulatory constraints, the bacteria are liberated to produce cellulose at heightened levels.

This discovery raises fascinating questions about genetic regulation in microbial production systems and suggests broader applications in industrial strains aimed at creating various non-protein materials. As Professor Studart aptly remarked, the methodology not only signifies a scholarly achievement but also represents a watershed moment within the field, as it pioneers new avenues for material production that extend beyond conventional protein synthesis.

Looking Forward: Potential Industrial Applications

The implications of this research extend well past the lab bench. The team has already taken steps to patent their innovative methodology along with the newly developed bacterial variants. Plans for future collaboration with industrial partners specializing in bacterial cellulose production are currently being outlined to facilitate real-world applications of these advancements. As the field of biotechnology continues to evolve, such pioneering efforts can equate to tangible benefits, providing sustainable materials that could significantly reduce our dependence on traditional manufacturing practices fraught with environmental concerns.

In closing, the ongoing exploration of bacterial capabilities underscores the untapped potential that microorganisms present in modern manufacturing. By harnessing the transformative power of bacteria, we stand on the precipice of a new era in sustainable material production—one that could reshape our ecological footprint and innovate how we interface with the natural world.

Leave a Reply