In a groundbreaking study conducted by a research team from Rutgers University-New Brunswick, scientists have unlocked a treasure trove of data buried deep within coastal sediments, revealing storm histories that span over 400 years. This innovative research sheds light on a previously overlooked method of understanding past hurricanes, enhancing our comprehension of how climate change could potentially alter storm frequencies in the future. The study, prominently featured in the Journal of Quaternary Science, demonstrates the significance of geological records in piecing together the intricate puzzle of nature’s violent storms, particularly at New Jersey’s Cheesequake State Park wetlands.

The scientists discovered eight distinct storm deposits located within sediment layers beneath the wetlands. Remarkably, some of these deposits date back to 1584, well before the advent of modern instrumental records. Kristen Joyse, the study’s principal investigator and a doctoral graduate of Rutgers, emphasizes the importance of delving deeper into geological timeframes: “These sediment records allow us to look much further back in time than current instrumentation allows us.” Her work underscores how sediment analysis can provide a wider perspective on historical weather patterns, significantly enriching the narrative of past hurricanes.

Beyond Conventional Measurements

Traditionally, researchers have relied on tidal gauges—strategically placed sensors that monitor water levels along coastlines—to track past storm activity. While effective for short-term analyses, this approach ultimately limits our understanding of more remote, significant storm events. Joyse articulates this limitation: existing records often rely on variables like shipping logs or newspaper archives, which are insufficient for encountering severe weather events that predate modern documentation.

The introduction of overwash deposits—sedimentary layers created when hurricane surges push coastal sand into wetlands—provides an opportunity to revisit previous storm events. Such events, being natural geological phenomena, may serve as a clearer indicator of storm history than available tidal measurements. To validate the findings, the research team analyzed their sediment samples in relation to available tidal records, determining the “preservation potential” of storm deposits, which is critical for discerning the reliability of geological evidence in climate studies.

Pioneering Research Methodologies

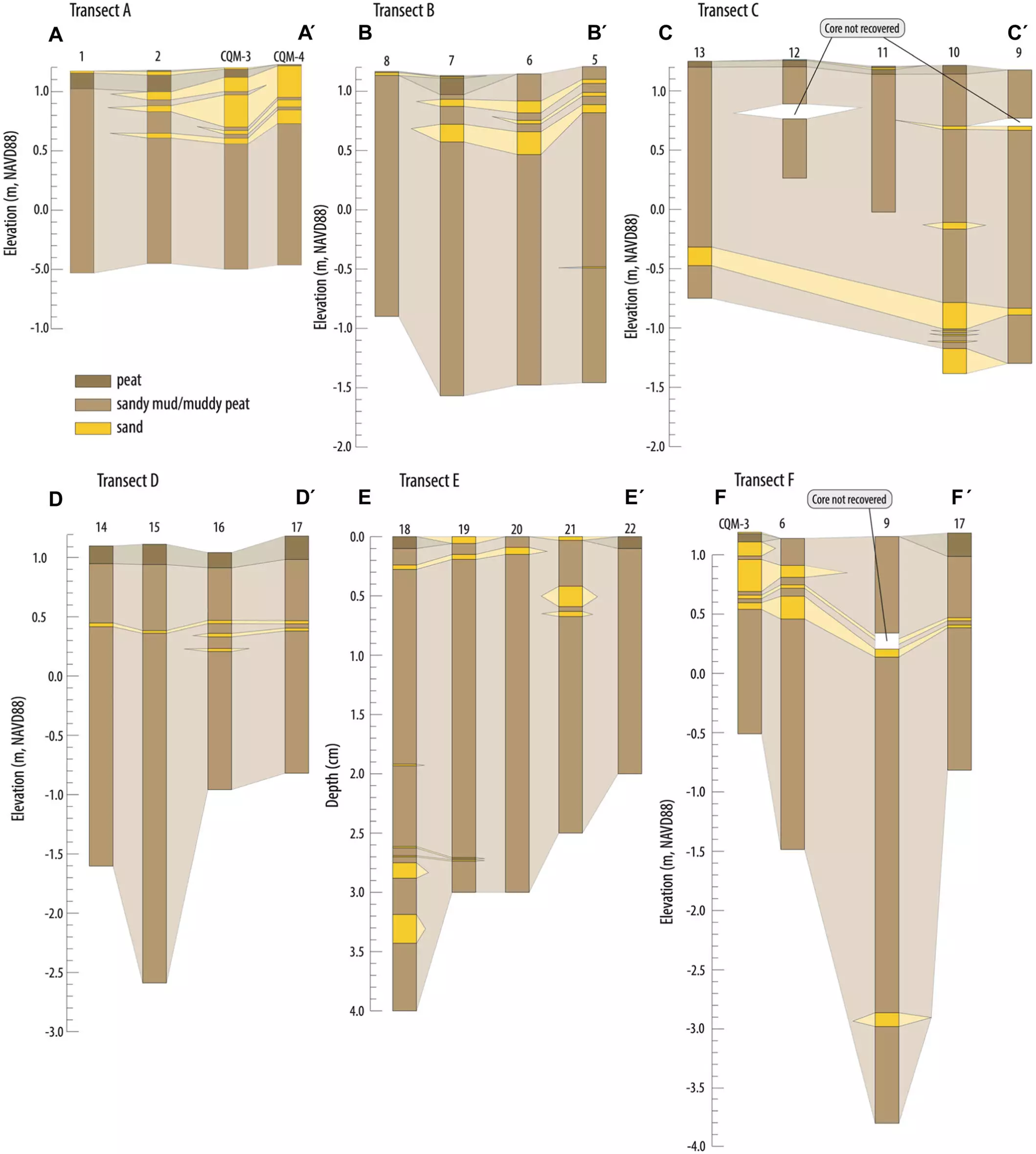

The geological investigation involved examining sediment cores, some reaching depths of eight feet, from diverse environments ranging from peaty to sandy regions. Through meticulous analysis encompassing grain size, organic materials, microfossils, carbon isotopes, and even heavy metal concentrations, the research team effectively distinguished between the sandy layers indicative of storm activity and the baseline wetland sediments.

Their findings were striking. The sediment cores revealed evidence of severe storms that predated instrumental records, including significant hurricanes such as the one in 1788 and another in 1693. Joyse’s work reinforces the notion that through sediment analysis, we can date events long before any formal meteorological reporting, thus enhancing our grasp of historical climatology.

Implications for Future Storm Patterns

Furthermore, the research posed critical questions about the relationship between storm preservation in sediments and climate variables in flux. By analyzing past storm data alongside tidal records from the longest-operating gauge systems in the United States, the team concluded that while significant hurricane events were accurately identified through sediment samples, the records do not encompass all extreme weather occurrences that tidal gauges detect. Notably, the Sandy Hook gauge captured additional events that were absent from sediment records.

Robert Kopp, a co-author and distinguished professor at Rutgers, highlights the implications of these findings. “These records allow us to look much further back in time, and we just have to acknowledge that they don’t capture every extreme storm that makes landfall.” His insights reflect a critical juncture in geological science; acknowledging limitations while simultaneously celebrating the broader implications of excavating past climates.

Charting the Course for Future Research

This research not only reaffirms the necessity of examining sedimentary data but also opens avenues for further inquiry into storm preservation dynamics. Joyse poses provocative questions: Why are certain storms recorded while others mysteriously vanish? How may the likelihood of a storm being preserved in geological records shift over time and under varying climatic conditions?

With several co-authors, including leading voices from various institutions, this study establishes a collaborative framework for future investigations. Their collective expertise may pioneer a new era in environmental science, one that comprehensively grapples with the intertwined fates of storm activity and climate change. The study’s revelations compel us to reconsider the reliability of traditional records and to embrace new methodologies that may redefine our understanding of the planet’s tempestuous history.

Leave a Reply