The study of collective movement has long intrigued scientists, bridging disciplines as varied as physics, biology, and social sciences. Recent research has illuminated an unexpected relationship between the behaviors of seemingly disparate entities, such as flocks of birds, crowds of people, and even groups of cells. Contrary to the belief that biological systems operate on principles fundamentally different from those governing atomic structures, evidence suggests that the laws of collective dynamics remain consistent across these forms. An interdisciplinary study involving researchers from MIT in Boston and the CNRS in France published in the Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, posits that humans, birds, and self-propelled biological agents can be analyzed through the lens of statistical physics akin to particles in a material.

Julien Tailleur, a biophysicist at MIT, articulates a compelling analogy: “In a way, birds are flying atoms.” This observation posits that the rules governing the movement of crowds and the flight of flocks share intrinsic similarities with the behavior of atoms and molecules. Traditionally, scientists have admired a stark division between the interactions of particles, which primarily depend on physical proximity, and those of biological units, which align based more upon visual cues and cognitive limits. This distinction, they believed, fundamentally influenced the transition between chaotic and organized states—known as phase transitions—among these systems.

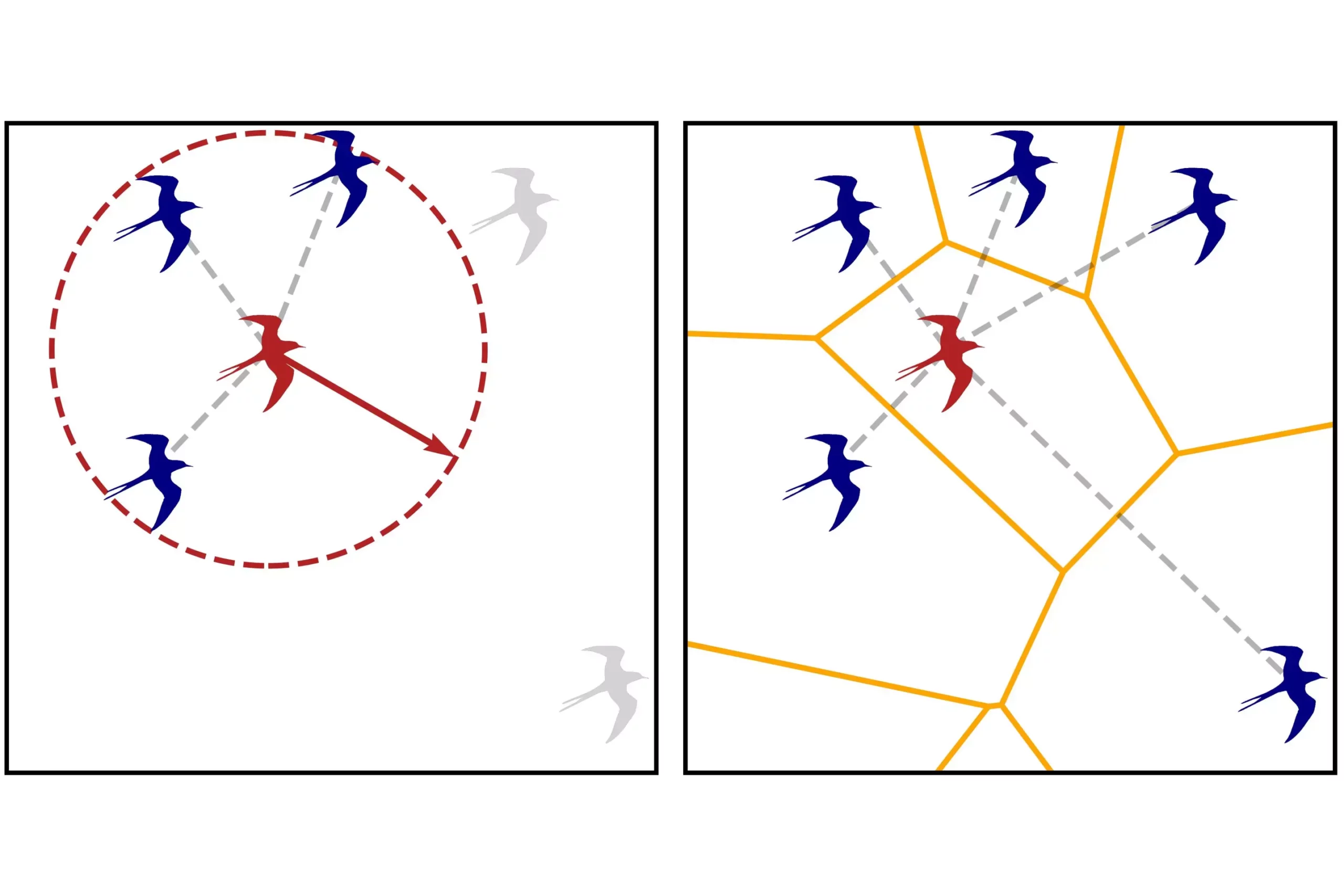

However, as revealed by their findings, Tailleur’s team challenges these long-accepted notions. They emphasize that, while the nature of interactions between particles hinges on spatial distance, for self-propelled entities—like a pigeon navigating its flock—what holds significance is the visibility and connection with others in the same perceptual field. Thus, biological entities may engage in a “topological relationship” with their environment. This implies that two birds, though distanced far apart physically, can significantly influence each other if they occupy the same visual space, contrasting the strict geometric dependency found in atomic systems.

Amidst these intriguing findings lies a recognition of the limitations and complexities inherent in biological systems. While acknowledging that their model simplifies reality—eliminating myriad factors influencing behavior—Tailleur underscores the importance of abstraction. The objective, in the spirit of Einstein’s wisdom, is to simplify phenomena “as much as possible, but not simpler.” This mantra encourages researchers to strip away extraneous complexities while retaining critical elements essential for analyzing the essence of collective motion.

Their innovative model draws inspiration from ferromagnetic materials, known for their magnetic properties. The behavior of such materials exemplifies how the alignment of spins varies with temperature and density: at elevated temperatures, spins arrange chaotically due to thermal fluctuations, whereas lower temperatures foster ordered arrangements. Such principles resonate with what is observed in biological agents, where collective motion aligns unexpectedly.

Historically, it was thought that collective behavior in biological models—where entities align with their topological neighbors—would reflect a gradual or continuous transition. Instead, Tailleur and his colleagues uncovered that similar conditions yield a discontinuous transition, mirroring the behavior observed in passive ferromagnets. This breakthrough implies that the models employed in statistical physics can seamlessly apply to study biological collective movement, fostering a deeper understanding of how various systems transcend their apparent categorical divides.

The implications extend beyond simple comparisons; they open avenues for multidisciplinary dialogue among physicists, biologists, and social scientists. The ability to employ statistical models of particles to analyze biological systems signals a significant advancement in creating unified frameworks for understanding phenomena that were once thought to exist in isolation.

As this line of inquiry continues to evolve, the potential applications are vast. Understanding collective movements—be it in the context of migration patterns in birds, the dynamics of pedestrian crowds, or even the behavior of cells in swarm formations—holds the promise of enhancing various fields, including ecology, urban planning, and medicine. Future research could delve deeper into the nuances of these interactions, perhaps addressing how external factors like environmental disturbances impact movement and cohesion.

The work undertaken by Tailleur and his colleagues exemplifies the generative potential of interdisciplinary exploration. By revealing that the principles underlying collective motion are not all that disparate between physical and biological realms, they may soon change the way we approach and solve problems related to the behavior of complex systems. The fusion of physics and biology not only enriches our comprehension of nature but also enhances our ability to predict and manipulate the dynamics at play in our environment.

Leave a Reply