Anorexia nervosa stands as one of the most debilitating mental health disorders, characterized primarily by drastic weight loss, an intense fear of gaining weight, and distorted body image perceptions. This multifaceted condition not only impacts physical health but also carries significant psychological burdens, leading to heightened risks of anxiety and depression. Though the full mechanisms behind anorexia remain elusive, recent findings highlight the potential role of neurotransmitter function changes, possibly paving the way for improved treatment methodologies.

Traditionally, anorexia nervosa has been associated with severe malnutrition and troubling psychological symptoms. However, growing evidence suggests that alterations in brain chemistry could be a pivotal factor in the disorder’s development. A recent study underlines the involvement of a particular receptor type known as the mu-opioid receptor (MOR), which seems to play a crucial role in the regulation of both pleasure-related eating behaviors and those necessary for sustenance. This aligns the condition not merely with the conscious decisions of an individual but implicates biological systems deeply rooted in the brain’s reward processing.

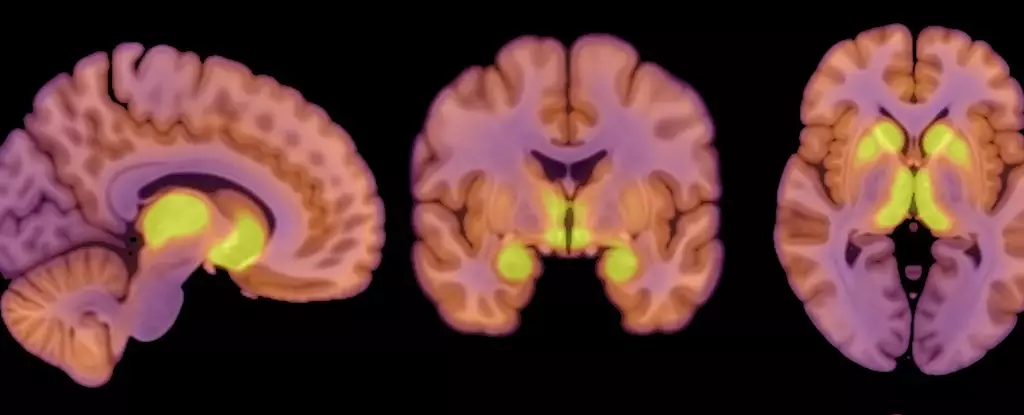

Research indicates that in individuals battling anorexia, there is an increased availability of MOR in regions of the brain associated with this reward system. This heightened presence is juxtaposed with findings in obese individuals, where a lower availability of these receptors is noted. According to Pirjo Nuutila, a physiologist at the University of Turku, this suggests a dual mechanism at play where both loss and gain of appetite may be influenced by the activities of these opioid systems.

The study included 13 females diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, with BMI measurements indicating significant underweight classifications. They were compared with a control group of healthy females, thus ensuring that any observed differences could be attributed to the condition itself rather than general variances in female physiology. Positron emission tomography (PET) provided key insights into how the patients’ brains processed glucose, offering a window into how restricted caloric intake affected their neural functions.

Interestingly, the research revealed that the brains of anorexia patients utilized glucose at levels akin to those observed in their healthy counterparts. This underscores a critical aspect of brain priority: even in a state of starvation, the brain attempts to maintain its functionality, striving to preserve its energy supply.

The research suggests that the up-regulated MOR may serve a vital role in understanding anorexia. Given that the raised availability of these receptors correlates with the dysfunctional relationship with appetite and food intake in anorexia patients, it hints at a more complex interplay between brain chemistry and disordered eating behaviors. The observation of this “mirror image” effect in obesity further stresses the nuanced relationship between weight, appetite, and brain function.

However, the study does recognize important limitations that temper the findings. The exclusive focus on female participants necessitates caution in generalizing the results to males, given the predominantly female prevalence of the disorder. The small sample size, while providing insight, limits the robustness of the conclusions. Moreover, the absence of a detailed questionnaire on eating behaviors restricts connections between MOR availability and individual eating patterns.

The fundamental query of whether the modifications observed in the opioid systems are causative or consequential to anorexia is a vital one that remains unanswered. The researchers emphasize the necessity for additional, more expansive studies that could encompass diverse patient demographics and methodologies, particularly those that examine the psychological dimensions entwined with the physiological aspects highlighted.

The compelling links emerging from this research not only enhance our understanding of anorexia nervosa but also evoke hope for the future of treatment options. The ongoing exploration of how brain function and neurotransmitter systems contribute to both obesity and anorexia could yield significant revelations in the pursuit of effective interventions. As Lauri Nummenmaa points out, an intricate relationship exists between brain function, appetite regulation, and body weight—a relationship that may unlock new dimensions in addressing the complexities of eating disorders like anorexia nervosa.

Leave a Reply