When an individual’s heart stops, every second counts. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can significantly enhance the chances of survival during a cardiac arrest, an event where every minute feels like an eternity. By maintaining blood circulation to the brain and vital organs, CPR provides a crucial lifeline until professional medical help arrives. Yet, recent studies have unveiled a disturbing trend: gender bias impacts the likelihood of receiving CPR, with bystanders often less willing to intervene when the victim is female. This discrepancy begs the question—could elements of CPR training itself inadvertently contribute to this bias?

Analyzing data from a comprehensive Australian study spanning 2017 to 2019, researchers found that bystanders were 9% less likely to administer CPR to women than to men. While CPR techniques remain largely the same regardless of anatomy, the hesitance to perform life-saving interventions based on gender can have fatal consequences. This is particularly alarming considering that cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death for women globally. Women suffering cardiac arrest outside of hospital settings face a daunting statistic: they are 10% less likely to receive CPR compared to their male counterparts.

The implications of this bias extend beyond immediate survival. Studies indicate that women not only receive CPR less frequently but are also at a heightened risk of suffering from brain damage as a result of delays in intervention. Such disparities underscore an urgent need for change, as they reflect underlying gender biases that can affect care outcomes.

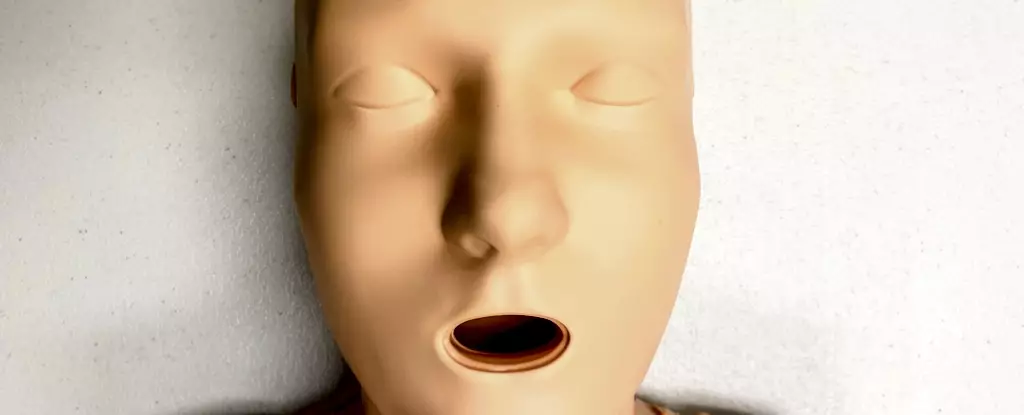

An exploration of CPR training practices reveals an alarming tendency to rely predominantly on male-oriented resources. A significant contributor to the gender bias in CPR performance may stem from the training manikins used worldwide. Research indicates that 95% of CPR training manikins are flat-chested, suggesting a clear inclination toward male representation in educational materials. While the presence or absence of breasts does not matter for the mechanics of CPR, it does influence bystanders’ perceptions in real-life situations.

Studies indicate that individuals trained with male-dominant manikins may internalize the notion that CPR is primarily a male-rescue role. This “default” representation could heavily influence a bystander’s decision-making process in emergencies involving women. Further compounding this issue is the longstanding association of women with being “fragile,” leading some potential rescuers to hesitate out of fear of causing harm or because they feel uncomfortable touching the victim’s body.

To combat the biases prevalent in CPR response, a concerted effort is needed to address the existing training materials. Only 25% of the CPR training manikins available in 2023 were marketed as female, and only one had anatomical features resembling breasts. This lack of diversity not only misrepresents the population but also perpetuates harmful stereotypes in life-saving practices.

The inadequacy of female and diverse representations in CPR training materials requires immediate attention. Infusing inclusivity into training practices—through varied body types and skin tones—can assist in preparing individuals to respond effectively in emergencies across genders. It is vital for training scenarios to reflect the diversity of real-life situations so that potential rescuers feel confident and prepared to act, irrespective of the victim’s gender.

To break down the barriers of hesitation, education surrounding cardiac arrest symptoms must be prioritized. Recognizing signs such as lack of breathing or responsiveness should be universal across all genders, reinforcing the message that prompt action is critical, regardless of the perceived fragility of the victim.

CPR training should cover the simple yet crucial steps involved: positioning hands correctly, maintaining consistent push rates, and understanding when to use defibrillators—all without the anxiety stemming from gender biases. Importantly, while removing clothing may be necessary for effective defibrillator use, individuals should be trained that such actions should not delay critical care.

The disparities in CPR administration between genders highlight the need for systemic changes in how we approach life-saving training. By prioritizing diversity in training resources and reducing the stigma tied to gender-specific perceptions, we can ensure that all individuals have an equal chance of receiving potentially lifesaving assistance. A future where every participant feels empowered to act, regardless of the victim’s gender, may well be the difference between life and death. It is time we collectively reassess our approach to CPR training, fostering an environment that values inclusivity and responsiveness over outdated biases.

Leave a Reply